Text of the speech delivered at the funeral of Kees-Jan Brons at the Thomas Church in Amsterdam on Friday 17 November 2023.

The philosopher Hegel is reported to have said on his deathbed, “There is only one man in the whole world who understood me, and he misunderstood me.” There is a lesson to be drawn from this. There is, I think, a great risk involved in any attempt to explain Kees-Jan Brons’ philosophical work, to make it understandable. And that risk is certainly something that Kees-Jan himself has recognized. He says so in one of his latest articles, “Yet Hegel measures his teacher Kant too much by the vision he himself wants to put into words.” There is a risk that I measure my teacher Brons too much by the vision I myself want to put into words.

Kees Jan also did not want followers who would slavishly imitate him. And it is certainly true, let me confess it as a personal sin, that in the nearly 50 years in which I have known Kees-Jan, although I have tried to understand his intentions, his projects, I have certainly also and perhaps mainly been interested in applying what I had learned from him within my own questions and projects.

47 years ago, I got to know Kees-Jan Brons. First, as the philosophy teacher who distinguished himself from many others by the great seriousness and passion with which he practiced his subject and the extreme accuracy with which he read and explained texts. He soon became my mentor, with whom I spent much of my academic studies. When I started studying theology alongside philosophy, he proved to be a valuable interlocutor in that other subject as well. After all, he had also worked with the Dutch Mennonite professor Oosterbaan and was familiar with the writings of the theologian Karl Barth. Then a friendship developed, which sometimes went a long time without contact, and then suddenly blossomed again. I remember conversations about Lévinas and Husserl when I lived in Bussum. Conversations about Karl Barth when I lived in Lelystad, the relationship between Kant and Hegel everywhere and at all times, the possible value of being a pastor as a profession in modern times when I lived in Bussum and IJmuiden, conversations also about whether an attitude of faith was appropriate to a philosophical grounding. Thinking within a tradition with its handed-down propositions was not simply acceptable to him. Often and in various ways, he has asked whether the content of my teaching within the various churches where I have been pastor was not too stilted, too unreflective.

When Rudi te Velde and I were allowed to have a final conversation with him last Thursday, that was one of his concerns. He put us in charge of conducting this farewell service, with this very indication: “A certain openness is needed, a great firmness is not desirable.” And when I asked him if it should then still be a real worship service, he was adamant in his answer. Yes, a worship service, because faith had always been of great importance to him and certainly now. I would have liked to ask him what exactly he meant by faith. The only clue I had and have was the statement he made when I announced to him that I had chosen to become a pastor. “That’s nice,” he said, “then you are concerned with people’s personal truth.” Did he understand it that way for himself? Faith as a personal attitude of openness and trust? Would it have been something like a personal truth for them besides found and argued truth? A truth that perhaps could not easily be put into words precisely because any firmness was out of the question?

Friends, students, and colleagues will each have a view of how Kees-Jan influenced each of us. And the wonderful thing is that I think he influenced each of us differently. In conversations, he was often focused on what each of us needed to take the next step. Wasn’t there always that question at the beginning of a conversation: what are you working on now?

In the same way Kees-Jan interacted with his students, he also interacted with people around him. He had the rare ability to make contact easily because of his great charm and willingness to listen to problems. On the other hand, he also distanced himself easily, breaking off contact with people he didn’t like, people about whom he could also sometimes be harsh and critical.

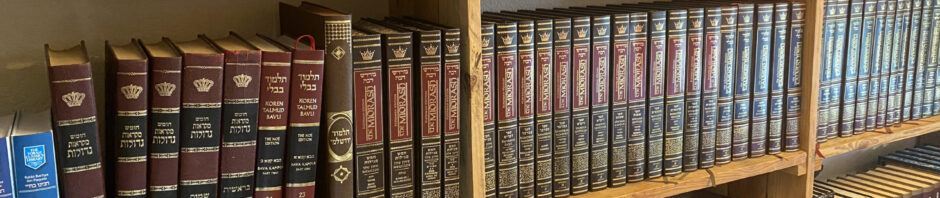

His main influence on us all, I think, and this is one of the outstanding qualities of his thinking, was his accuracy in reading texts. He once said that the purpose of interpreting a text lay in achieving a transparency of the text through which the matter at hand could be formulated in a pure way. The matter itself emerges from the well-understood text. He also sometimes used the word “toedracht” (difficult to translate: something like the real event considered from all possible angles), to indicate the reality of a being, a word that some of his colleagues felt was inappropriate, but which I – and others – gladly adopted.

But what then is the ultimate issue that emerges in Kees-Jan’s texts when we try to read after his fashion? It cannot fail to be that that matter will always be linked back to what we ourselves are trying to put into words. And then we are back to the inevitable misunderstanding of the actual, the essential thing Kees-Jan had in mind.

Perhaps it was this: facing the project of modern philosophy from Hegel onwards, showing the importance of focusing on being as being. What the real self was, without an external determination of its objectivity. Perhaps it is this: to bring about the understanding of the inner movement of modern philosophy and its project. Or perhaps it is this: showing that in the face of postmodernity, it is worth upholding the intrinsic value of human personality and self-consciousness. All these attempts to put the issues, his issues, into words betray something of the influence of a vision of my own. Yet I heard him defend each of these statements in one way or another.

As strict and precise as he was in explaining texts, he could also be so in dealing with other people, institutions, and even family members. Always probing, getting to the bottom of something, not resting until the only correct answer was found. That must not always have been easy for the children in the family. For it took strength and perhaps even courage to hold your own against his critical spirit.

Sometimes a little less would have been better. When I announced 30 years ago that I had started a reading group on the philosopher Schelling with some friends, he started to question me. What exactly was the purpose of this group? What was the issue we sought to clarify with the aid of Schelling? In short: why Schelling? I stammered some answers, got red in the face, and nothing more came of the reading group. Because I didn’t know the purpose, and I couldn’t answer the question of what I was actually looking for in Schelling. The project collapsed. Because that’s how it was with me – and probably with others too – if the project died under Kees-Jan’s critical attention, there was no resurrection. Yet I never resented that. After all, as annoying as that was, he was usually quite correct. Perhaps this is recognizable to many. As warm as my feelings could be for him, I was also always a bit shy because he could also make such harsh judgments.

All that notwithstanding, I always enjoyed the visits to his house, and meeting not only him but also his wife Marijke. Her presence also always took away some of the tension, and besides, she was the only one who would get me a cup of coffee. Because he didn’t do such things.

May Kees-Jan now rest in the arms of the God about Whom we may not be certain, but Whom we still may invoke in an unfounded, but no less powerful trust.